Richard Avedon’s view of Francis Bacon

Francis being photographed

Francis Bacon - Richard Avedon

The interaction of the photographic document and the portrait

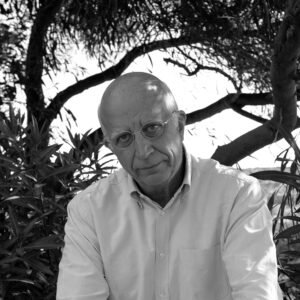

Richard Avedon was born in New York through 1923 and spent the majority of his life there. His interest in photography began at a young age and peaked during his military service as a photographer in the United States Merchant Navy.

“It was my job to take ID photos.” “I must have photographed a hundred thousand people before I realized that this was how I became a photographer,” he explained later, explaining how he came to pursue photography professionally.

His portraits are among those that, whether you like it or not, force you to mentally participate in the process of visualizing the subject, delving into the how’s and whys, when and where, by whom and for whom.

He got into fashion by photographing for major American magazines like Harper’s Bazaar, where he was the main photographer for several years. He resigned in 1965 after being chastised for his collaborations with color models.

He collaborated and did many portraits for the magazines Theater Arts, Life, and Look, while Vogue managed to keep him for twenty years, creating extraordinary campaigns where Avedon’s portrait photos became real documents through their collaboration.

He was hired as the head of the photography department at The New Yorker in 1992, giving the magazine a new impetus through his portraits, which led to a redefinition of its subject matter and philosophy in general.

His story appears to be as endless as the photographs he took over the course of his creative career. His long association with Calvin Klein, Revlon, Versace, and dozens of other companies resulted in some of America’s most famous advertising campaigns.

Portraits of the American civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, and his father, Jacob Israel Avedon. The Family was a massive project for Rolling Stone magazine, involving portraits of America’s political elite on the occasion of the country’s bicentennial celebration.

Artists like the Beatles, Marilyn Monroe, Buster Keaton, Andy Warhol, and dozens more became objects of desire for Avedon’s photographic lens. For him, a photograph could capture every aspect of the person being photographed’s personality and soul.

He could see into the people he photographed, arousing their emotions and stimulating their senses. He has become argumentative on purpose at times, causing them to react negatively.

His portraits are minimalist in style; he exalts from the all-white background without using soft lighting, forcing his models to face his lens. He converses with them, revealing aspects of their character and personality, illustrating not only the appearance but also an internal invisible structure, what is hidden behind the look, expression, and body posture.

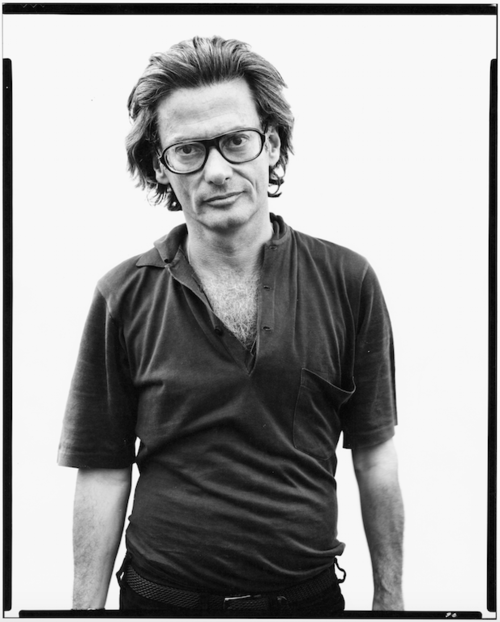

Francis being photographed

Richard Avedon combined two different negatives from his portraits of Francis Bacon in 1979. In the same year, Avedon’s friend and painter had already prepared two studies of himself using the same logic, in order to complete his self-portrait.

Bacon himself created dozens of exceptional portraits, both on a single surface and in diptychs or triptychs, classifying his works in series. So, once again, Avedon’s photographs combine to form a single work in which the union is visible. It makes no attempt to conceal the fact, and the different styles of the individual frames are felt even more strongly.

Bacon is depicted as a “bust” (bust) on the left, and a vertical view cut into three quarters on the right. The painter is kept in the foreground by the blindingly white background, giving the impression that the black-clad figure emerges from the void.

Avedon does what he does best: he initiates a conversation with his model, inserts it into the story he is creating, and begins the narrative. He is not only interested in the “decisive moment,” but also in creating a document that will stand the test of time.

He wants to give in to the thoughts of the person in front of him, to make him react in any way in front of his camera, to “weary” him, to enrage him, to make him believe that no matter how his image is captured in the photosensitive surface, a unique story will be created.

The photographs are very similar to Bacon’s painted portraits such as they contain the sadness, perhaps even horror, that the painter expressed through his dark works, wanting to make fun of himself, to raise questions by highlighting the cruelty of the “small” human existence filled with passions and decay.

Avedon does not create any conditions, he dislikes the “bullet,” he allows his camera to travel through his friend Francis’ movements and characteristics in order to freeze the unexpected, the momentary – which may appear “wrong” – and leaves the background blank.

He dislikes the background noise and concentrates on the expression, movement, and dialogue that his model initiates with the lens, intent on opening the hatch of emotions and filling the space of the photographic frame with them.

Bacon directs himself and gives Avedon’s lens an exquisitely aesthetic photographic effect that will stand as an indisputable testament to the two artists’ inexhaustible talent.

He raises his hands to the forehead, cheekbones, near the mouth and lips, creating fragments of a narrative form that are eventually captured by Avedon’s “intelligent” lens.

Bacon’s controversial personality finds explanation in Avedon’s gaze to drag her into a one-of-a-kind performance in which the two of them will star with the goal of recording a theatrical monologue whose protagonist does not seek to hide anything.

Instead, he allows his first thoughts to form, mocks himself, goes limp for a moment, and then immediately redefines his posture and facial expression, imbuing the image with the cursed sense of mourning that Bacon so adored.

He depicted it in every way imaginable, with every stroke, shade, shadow, and illumination. He thus transferred his own psyche to Avedon’s photographs, which are now admired not only as outstanding portraits but also as records of a revelatory creative collaboration._